For most clients, I provide detailed performance reports quarterly – anything more frequent is subject to too much volatility, but on the other hand most people like to see how everything is performing more often once or twice a year. Quarterly feels about right.

As a new business, I have set up a benchmark portfolio, which I will also track and report on quarterly. While this portfolio will not match any client’s portfolio exactly, it does provide an indication of how the Nest Egg Investments Investment Principles play out in the real world.

The benchmark portfolio falls into the growth category of portfolios (typically suitable for investors with a timeframe of 8+ years), and consists of:

65% growth assets:

- Australasian shares 19%

- Global shares 33%

- Emerging markets shares 6%

- Commercial property 7%

35% defensive assets:

- NZ fixed interest 15%

- Global fixed interest 15%

- Cash 5%

Within the above allocations are a mix of passive funds (very low fees, track an index), structured passive funds (similar, but overweight in particular attributes, eg. value stocks or small cap stocks), and carefully chosen actively managed funds. There are 9 funds used in total, plus term deposits for NZ fixed interest, plus cash.

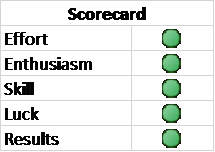

The results for the first quarter of 2017 (1-31 March), in NZ$, after all fees (fund fees, platform fees, adviser fees) but before tax are as follows:

- Australasian shares: +8.0%

- Global shares: +7.1%

- Emerging markets shares: +12.6%

- Commercial property: +2.0%

- NZ Fixed interest: +0.8%

- Global fixed interest: +1.1%

- Cash: +0.2%

- Overall portfolio: +5.3%

This is an excellent result for just one quarter, with all sectors positive, and certainly reflects a good start to the year for equity markets worldwide, plus a weaker NZ$ (which helps performance). Emerging markets was the stand out performer (see my earlier blog The case for Emerging Markets). The actively managed funds in the benchmark portfolio overall outperformed the passive/structured passive funds by about 10%.

Its important to note that this is a theoretical portfolio, and the performance will not always look this good. Still it is a great start! I will report again after Q2.

Dean Edwards